Line Lyhne

A fussiness inside

Mar 23-May 04, 2024

Line Lyhne’s first solo exhibition at Petra Rinck Galerie is a celebration of fussy attention to detail and care. Terms that are historically associated with artisanal production and read as feminine and allegedly inferior manufacturing processes. Industrial production, however, is considered efficient and precise. Reflecting this binary cliché, the works in A fussiness inside give the impression of being mass-produced, as if they rolled off an assembly line, yet are meticulously handcrafted. The three work groups in the exhibition trace the pervasive veilings and mystifications of capitalism and the resulting alienation of people from their products and processes. In this way, the artist encourages a critical engagement with these terms and reassigns agency back to the materials themselves.

Lyhne’s work group Bürolandschaft (2023), consisting of geometrically minimalist steel sculptures, are modern ghosts from a post-Fordism past that have long since forfeited the promise of productivity, flexibility and availability. The sculptures are based on a modern, simple but highly functional design of office furniture, but are rendered non-functional at the same time. They appear as affectless shadow beings, spatial pencil drawings of their iconic predecessors. They cannot be used to sort files or categorize other objects. They give the impression of having been industrially manufactured, but are actually handmade by Lyhne. Round steel rods are welded into complex geometric bodies, all of which differ in height, width and depth and do not agree on a uniform form. The artist further individualizes each of her sculptures by integrating found objects such as keys, organic forms in the rods and handmade objects such as blown glass. The electrochemical or heat-based coatings, such as chrome plating or galvanizing, leave their marks. The artist exhibits these supposed defects and thus the process of material transformation. Bürolandschaft challenges the dualism of handmade and industrial production and opposes the common notion that industrial production is independent of workers, thus emphasizing the socio-economic perspective of industrial labour.

The artist positions her work in the concept of “Autoprogettazione” by Enzo Mari through the accessibility of construction. In 1974, the Italian designer published the first edition of “Autoprogettazione”, an instruction manual for a series of easy-to-assemble furniture pieces that could be made by anyone with the simplest of tools. The manual was based on elementary building plans and provided an understanding of the basic structural components of an object, but also encouraged users to execute the projects in different ways and customize details or shapes. Without pursuing Mari’s didactic approach, Lyhne’s processes critically engage with the industrial production contexts of her materials. Her sculpture is research through practice, critical understanding through making.

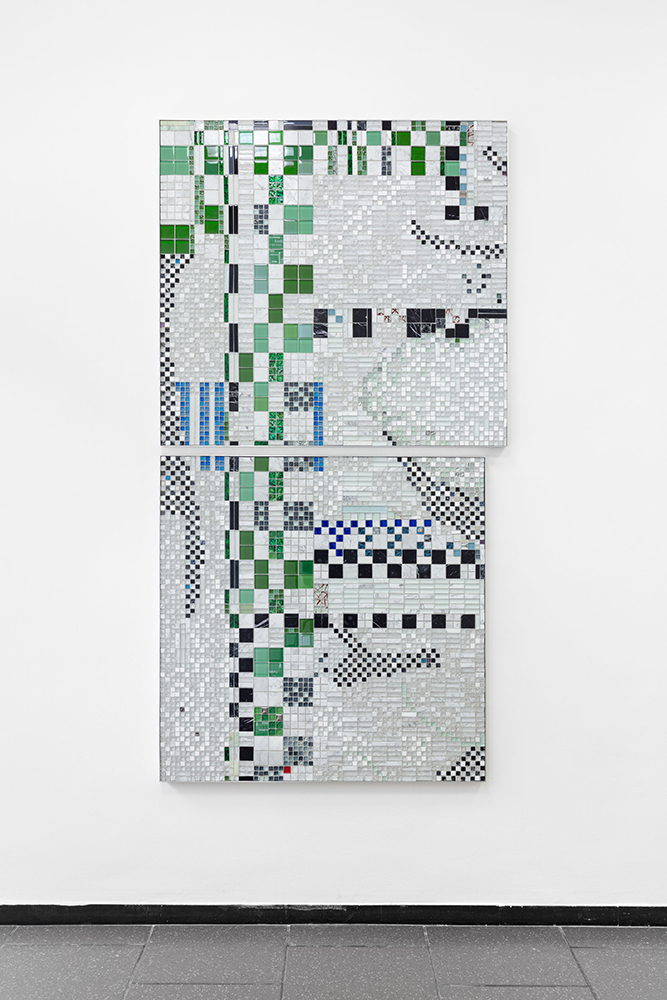

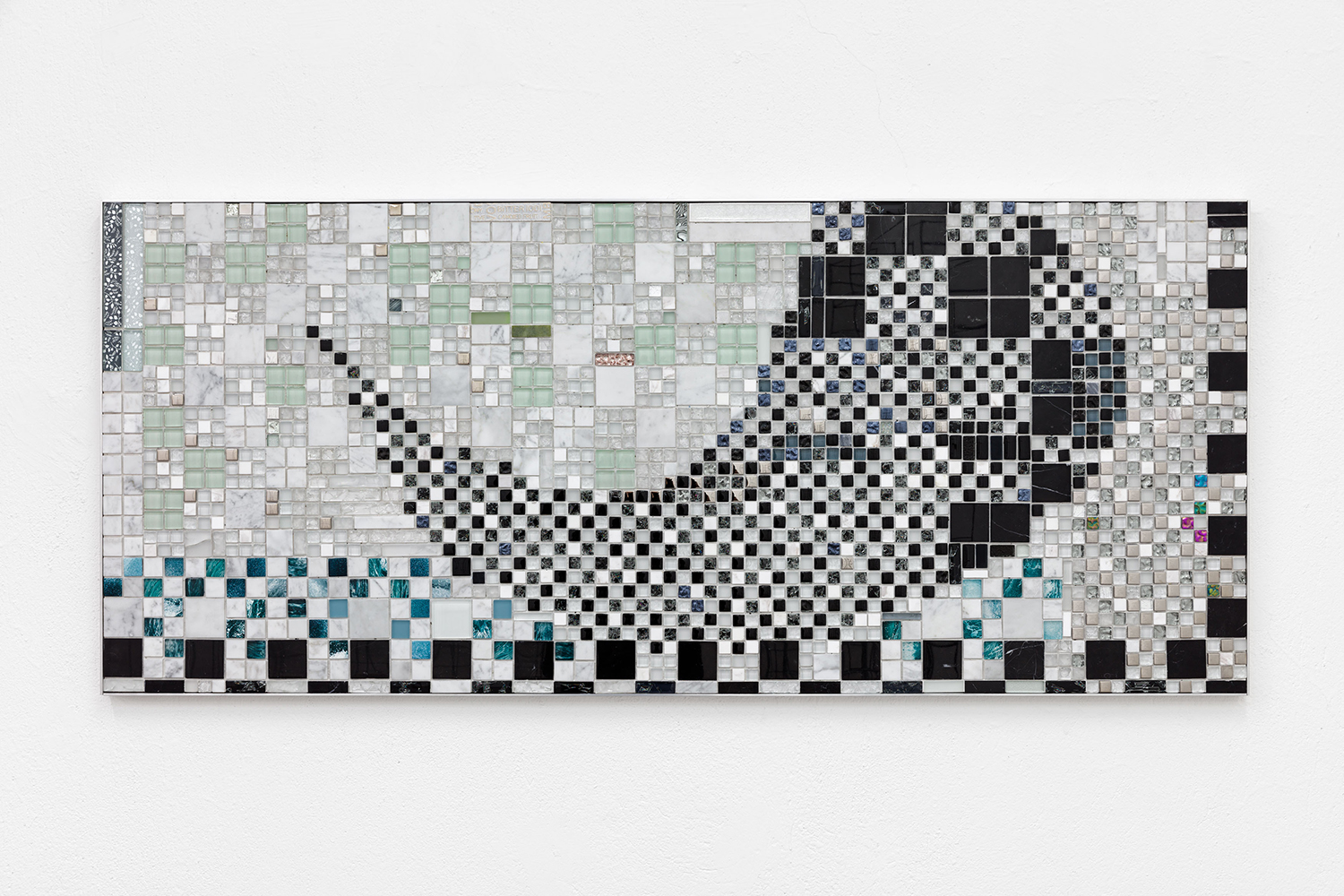

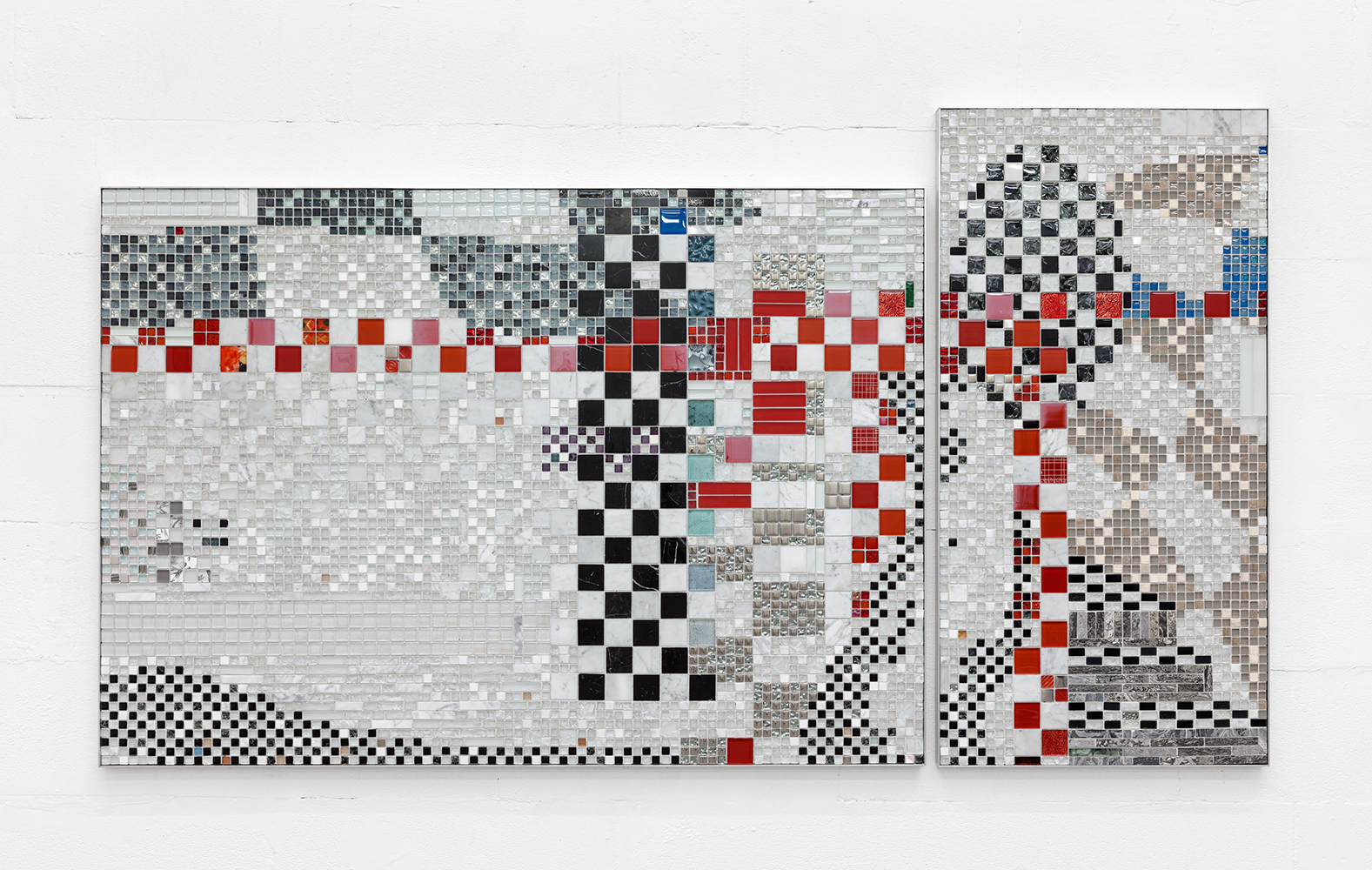

Making and method are also the focus of the second group of works, which comprises of tiled mosaics, of which four form two diptychs. Lyhne composes her abstract Reliefs (2024) from industrially manufactured tile slabs, which she disassembles and reassembles into her own constellations. In contrast to historical mosaics, in which the size of the individual pieces is not determined, Lyhne’s compositions are based on the smallest unit, the smallest industrially producible tile – a pixel. In this way, Reliefs, like digital imagery, are created on a grid. In keeping with Rosalind Krauss’s modernist grid, the artist thus creates the impression of order and lends her works a seriality through repetitive patterns, uniform structures and the possibility of reproduction. While these works have a handcrafted quality through their making, the grid in this case allows Lyhne to distance herself from personal expression to focus instead on the systematic exploration of form and space. The artist creates a sense of spatial ambiguity and permeability within the grid, despite its rigid appearance. By overlapping lines and meanings, manipulating scale and attributions, Lyhne destabilizes the viewer’s perception of space and challenges conventional assumptions on notions of depth, perspective and context.

Lyhne’s investigation of the social and cultural hierarchies of materials and objects, which is present in all of her works, is fleshed out in new stone sculptures. Entanglements (2024) are rough stone cuts from the quarry that become displays for small everyday objects such as keys, coins, pens and USB sticks. The artist has carved the shapes of these objects into the raw, uncut surface of the stones, so that they easily find their place, but also leave a moulded imprint in their absence. In the material encounter between stone and object, raw and finished material, their respective biographies, attributions and entanglements are revealed, merged and permeated. The stone appears as an anonymous fragment, as one among many. Its specific material properties disappear in the mass of the quarry and its personal qualities stem exclusively from the extraction industry. Its industrial origin is its only signifier. The everyday objects, on the other hand, are personally and culturally charged objects. They come from a specific household and have intimate relationships with people. They tell layered social stories of movement, purpose and emotion. By emphasizing their sociality, however, their political, economic and ecological contexts remain obscured. Lyhne complements and entangles the attributions and elisions of both parts, opening them up to alternative conceptions of matter and process and their exchange. Entanglements are material and conceptual amalgamations in which subject-object relations are reciprocal. In this way, stone and product are understood as equal parts of a global circulation of raw materials, resources and ideas.

In her work, Lyhne detaches material from its purely physical or even artistic field of reference and contextualizes it according to its non-artistic use: industry, market, circulation, extraction and labour. The artist’s acknowledgement of often hidden production contexts of the objects and materials she works with, coupled with the ambiguity she ascribes them, restores the complexity these objects and materials always had but are obscured by the capitalist mode of production. Her materials are shaped by historical, social and technological formations and developments, cultural contexts and individual perspectives. Lyhne’s concept of material thus becomes permeable to external influences and generates dynamic, creative and ethical relations. Fussiness is both Lyhne’s approach and matter’s innate complexity and agency.

Lyhne’s craft sensibility replaces industrial reproducibility in her work. Her work is at odds with the naivety of materials and the coherence of processes in the capitalist system. By laying her physical process bare in the works, the artist both highlights and further augments their plurality: corporeal and highly mechanical; bureaucratic and personal; private and social. They are orderly and structured, as well as playful and ambiguous. Lyhne’s sensibility manifests itself physically and releases unbridled energy. She exposes the notion of high and low art forms and highlights the differences in ideologies of value and taste. It is Lyhne’s very way of making that respects the vibrant character of matter and enables her to layer and intertwine complex levels of meaning.

Alke Heykes

Line Lyhnes erste Soloausstellung in der Petra Rinck Galerie ist ein Bekenntnis zur fussiness – zur kleinlichen Sorgfalt und Detailverliebtheit. Begriffe also, die überwiegend mit handwerklicher Herstellung in Verbindung gebracht und historisch auch als weiblich und angeblich minderwertig gelesen werden. Industrielle Fertigung hingegen gilt als effizient und präzise. Entgegen diesem binären Klischee erwecken die Werke in A fussiness inside den Anschein von massen-produzierten, vom Fließband gerollten Waren und sind dennoch akribisch von Händen gefertigt. Die drei Werkgruppen in der Ausstellung kommen damit den allgegenwärtigen Verschleierungen und Mystifizierungen des Kapitalismus und der damit zusammenhängenden Entfremdung des Menschen von seinen Produkten und Prozessen auf die Spur. Auf diese Weise regt die Künstlerin zu einer kritischen Auseinandersetzung mit diesen Begriffen an und überträgt den Materialien selbst wieder die Handlungsmacht.

Lyhnes Werkgruppe Bürolandschaft (2023) aus geometrisch minimalistischen Stahlskulpturen sind moderne Geister aus einem vergangenen Postfordismus, die das Versprechen von Produktivität, Flexibilität und Verfügbarkeit längst verwirkt haben. Die Skulpturen sind angelehnt an modernes, simples, aber hocheffizientes Design von Büromobiliar und sind gleichzeitig funktionslos. Sie sind affektlose Schattenwesen, räumliche Bleistiftzeichnungen ihrer ikonischen Vorgänger. In ihnen lassen sich keine Aktenordner sortieren oder andere Objekte kategorisieren. Sie erwecken den Eindruck industriell gefertigt worden zu sein, sind aber in Handarbeit von Lyhne und anderen gefertigt. Rundstäbe aus Stahl formen komplexe geometrische Körper, die sich alle in Höhe, Breite, Tiefe unterscheiden und sich nicht auf eine einheitliche Form einigen wollen. Die Künstlerin individualisiert jede ihrer Skulpturen weiter durch die Integration von gefundenen Objekten, wie Schlüssel, verschlungene Formen im Gestänge und handgearbeitete Objekte, wie geblasenes Glas. Die elektrochemischen und hitzebasierten Oberflächenbehandlungen, wie die Verchromung oder die Verzinkung, hinterlassen ihre Spuren. Die Künstlerin stellt diese vermeintlichen Fehler und damit den Prozess der Materialverarbeitung aus. Bürolandschaft fordert den Dualismus von handgefertigter und industrieller Produktion heraus und stellt sich gegen die gängige Vorstellung, dass industrielle Produktion unabhängig vom Menschen sei und hebt so die sozioökonomische Perspektive industrieller Arbeit hervor.

Die Zugänglichkeit ihrer Konstruktion verortet die Skulpturengruppe in das Konzept der „Autoprogettazione“ von Enzo Mari. Im Jahr 1974 veröffentlichte der italienische Designer die erste Ausgabe von “Autoprogettazione”, ein Konstruktionshandbuch für eine Reihe von mühelos zusammenbaubaren Möbeln, die von jedem mit einfachsten Mitteln, wie Holzbrettern, Hammer und Nägeln hergestellt werden konnten. Das Handbuch basierte auf elementaren Bauplänen und vermittelte ein Verständnis für die grundlegenden strukturellen Komponenten eines Objekts, ermutigte die Benutzer*innen aber auch, die Projekte auf unterschiedliche Weise auszuführen und Details oder Formen anzupassen. Ohne Maris didaktischen Ansatz zu verfolgen, versteht Lyhne ihre Verfahren als kritische Auseinandersetzung mit den industriellen Produktionszusammenhängen ihrer Materialien. Ihre Skulptur ist Forschung durch Praxis, kritisches Verstehen durch das Machen.

Die Machart und Methode sind auch in der zweiten Werkgruppe zentrale Aspekte. Reliefs (2024) sind Mosaike und umfassen zwei Diptychons. Lyhne komponiert diese abstrakten Werke aus industriell gefertigten Fliesenmatten, die sie zerlegt und zu eigenen Konstellationen zusammenfügt. Im Gegensatz zu historischen Mosaiken, bei denen die Größe der Einzelteile nicht bestimmt ist, basieren Lyhnes Kompositionen auf einer kleinsten Einheit, der kleinsten industriell herstellbaren Fliese – einem Pixel. Sie erstellt Reliefs, wie digitale Bilder, auf einem Raster. Dem modernist grid von Rosalind Krauss entsprechend, schafft die Künstlerin so den Eindruck von Ordnung und verleiht ihren Arbeiten eine Serialität durch sich wiederholende Muster, einheitliche Strukturen und die Möglichkeit der Reproduktion. Diese Werke haben zwar eine handwerkliche Qualität durch ihre Herstellung, das Gitter erlaubt Lyhne in diesem Fall jedoch sich vom persönlichen Ausdruck zu distanzieren, um sich stattdessen auf die systematische Erforschung von Form und Raum zu konzentrieren. Trotz des starren Erscheinungsbildes erzeugt das Gitter ein Gefühl der räumlichen Ambiguität und Durchlässigkeit. Durch die Überlappung von Linien und Bedeutungen, durch die Manipulation des Maßstabs und der Zuschreibungen destabilisiert Lyhne die Raumwahrnehmung der Betrachtenden und stellt konventionelle Vorstellungen von Tiefe, Perspektive und Kontext in Frage.

Die Untersuchung der sozialen und kulturellen Hierarchien von Materialien und Objekten, die in all ihren Arbeiten präsent ist, vertieft Lyhne in neuen Steinskulpturen. Entanglements (2024) sind rohe Steinstücke aus dem Steinbruch, die zu Displays für kleine Alltagsgegenstände wie Schlüssel, Münzen, Stifte und USB-Sticks werden. Die Künstlerin hat die Formen dieser Gegenstände in die rohe, ungeschliffene Oberfläche der Steine geritzt, so dass sie leicht ihren Platz finden, aber auch in ihrer Abwesenheit einen geformten Abdruck hinterlassen. In der Begegnung zwischen Stein und Objekt, Roh- und Fertigmaterial, werden ihre jeweiligen Biografien, Zuschreibungen und Verstrickungen offengelegt, verschmolzen und durchdrungen. Der Stein erscheint als anonymes Fragment, als einer unter vielen. Seine materiellen Eigenschaften verschwinden in der Masse des Steinbruchs und seine spezifischen Qualitäten stammen ausschließlich aus der Abbauindustrie. Sein industrieller Ursprung ist sein vermeintlich einziger Signifikant. Die Alltagsgegenstände hingegen sind persönlich und kulturell aufgeladene Objekte. Sie stammen aus einem bestimmten Haushalt und haben intime Beziehungen zu Personen. Sie erzählen vielschichtige soziale Geschichten von Bewegung, Bestimmung und Emotion. In der Hervorhebung ihrer Sozialität bleiben ihre politischen, ökonomischen und ökologischen Kontexte jedoch verborgen. Lyhne ergänzt und verschränkt die jeweiligen Zuschreibungen und Auslassungen beider Teile und öffnet sie für alternative Lesarten von Materie und Prozess und deren Austausch. Entanglements sind materielle und konzeptionelle Verquickungen, in denen die Subjekt-Objekt-Beziehungen dynamisch sind. So werden Stein und Produkt als gleichberechtigte Teile einer globalen Zirkulation von Rohstoffen, Ressourcen und Ideen verstanden.

In ihrem Werk löst Lyhne das Material aus seinem rein physischen oder gar künstlerischen Bezugsfeld heraus und kontextualisiert es entsprechend seiner nicht-künstlerischen Verwendung: Industrie, Warenhandel, Markt, Zirkulation und Arbeit. Indem die Künstlerin die oft verborgenen Produktionskontexte der Objekte und Materialien, mit denen sie arbeitet, anerkennt und ihnen Mehrdeutigkeit zuschreibt, stellt sie ihre Komplexität wieder her, die diese Objekte und Materialien schon immer hatten, die aber durch die kapitalistische Produktionsweise verdrängt wird. Ihre Materialien sind geprägt von historischen, sozialen und technologischen Formationen und Entwicklungen, kulturellen Kontexten und individuellen Perspektiven. Lyhnes Materialbegriff wird dadurch durchlässig für äußere Einflüsse und erzeugt wechselseitige, kreative und ethische Relationen. Fussiness – eine äußerst sorgfältige, fast kleinliche Dynamik beschreibt hier nicht nur Lyhnes Methode, sondern auch die der Materie innewohnende Komplexität und Handlungsfähigkeit.

Lyhnes handwerkliche Sensibilität ersetzt in ihrem Werk die technische Reproduzierbarkeit. Ihr Werk steht im Konflikt mit der Naivität der Materialien und der Kohärenz der Prozesse im kapitalistischen System. Indem die Künstlerin den physischen Prozess in den Werken offenlegt, unterstreicht und verstärkt sie deren Pluralität: körperlich und maschinell, bürokratisch und persönlich, privat und sozial. Sie sind geordnet und strukturiert, spielerisch und mehrdeutig zugleich. Lyhnes Sensibilität manifestiert sich körperlich und setzt kräftige Energie frei. Sie entlarvt die Vorstellung von hohen und niedrigen Kunstformen und hebt die Unterschiede in den Ideologien von Wert und Geschmack hervor. Es ist Lyhnes Methode, die den lebhaften Charakter der Materie respektiert und es ihr ermöglicht, komplexe Bedeutungsebenen zu schichten und miteinander zu verflechten.

Alke Heykes